One of the assignments I frequently give my students is to make a custom fixture based on a theme or on a design style. Here are a few of this semester’s best.

by Emily Roise

b;y San Hoi Lam

by Yan Cul

I’ve been hired to review an architect’s lighting design and then design an appropriate control system. The fixtures selected are all LED products by a manufacturer that falls into the high-end residential/economy commercial range of quality and price. The cut sheets are extremely frustrating. After nearly a decade of LED lighting, and with all of the progress the industry has made in setting standards so that designers and specifiers know what they’re getting, this manufacturer still tells us nothing. What basic information is missing?

Lamp life. The only information even remotely connected to lamp life is the statement that the fixture is covered under a five-year warranty. There’s nothing else. Not a word. How much light, compared to initial output, can we expect at that five-year mark? We have no idea.

LEDs do not fail like other lamps do. They gradually dim as they age. At what point is the light output so low that we’d say the lamp is no longer useful? Right now the answer is when the light output has fallen to 70% of the initial output (often referred to as L70), although many designers prefer to use 80% of initial output (referred to as L80). This is calculated using a procedure developed by the IES and designated as LM-80 (details are here and here). What we want, at a minimum, is the IES LM-80 calculation of lamp life to 70% of initial output. L80 data would be even better.

Warranty. The warranty is not on the manufacturer’s web site so, although we’re told that it is good for five years, we have no information about what is covered and what is excluded.

LED manufacturer. With all other lamp types the designer chooses the exact lamp for the project. Criteria such as initial lumen output, mean lumen output, lamp life, color temperature, CRI, and the manufacturer’s reputation for quality are all valid considerations. We have standards that allow designers to make valid comparisons between LED products, too, but we can do that only if that information is generated and shared. I suspect that this fixture manufacturer uses LEDs from a several manufacturers based on the best price available, and that the performance of those LEDs varies widely.

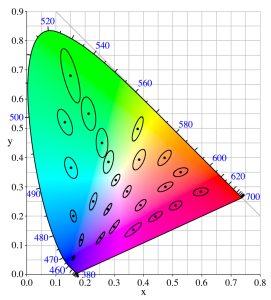

Color consistency. The cut sheet says that the standard applied to their LED selection is, “minimum 3-step color binning.” We are left to infer that means three-step MacAdam Ellipses. A one-step MacAdam Ellipse describes a region on a chromaticity diagram or color space where the edges of the ellipse represent a just noticeable difference from the color at the center (additional information on MacAdam Ellipses is here and here). The data is usually plotted on the CIE 1931 (x, y) chromaticity diagram. The diagram below shows 10-step MacAdam Ellipses.

The color variation within a three-step ellipse would be noticeable to over 99% of the population. Worse, though, is that a three-step ellipse is the minimum, not the maximum. Knowing this, the designer should have no expectation of color consistency from one fixture to another.

Photometrics. The cut sheet contains no information about the optical performance of the fixture. IES files are available, but it’s very difficult to look at the array of numbers and understand performance, which is why the good manufacturers include photometric information on their documentation, including candlepower distribution curves and CU tables.

Part of my review will be pointing out the lack of data about the specified fixtures and recommending several alternates by manufacturers who provide the information necessary to evaluate their products.

The main design assignment for this semester’s Pratt students is a cafe. The students selected their own interior design and had to develop a custom lighting fixture that is integrated with that design. Here area few of this semester’s fixtures.

One of my clients has expressed frustration with the caveats I place at the end of my lighting fixture budget. Why can’t I give the client a simple budget estimate? The answer is that fixture manufacturers don’t have a manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) for their products, which is something we’ve all come to expect for products ranging from potato chips to cars. We all know that things we want to buy have an MSRP or list price and it’s up to the seller to decide whether or not to sell at a lower price.

However, with lighting equipment the sales representative and the manufacturer collaborate to establish pricing for each project (see chapter 9). Larger projects with more luminaires will usually pay less per luminaire. This can be frustrating for everyone. It’s hard to develop a reliable fixture cost database when fixture costs are variable.

Another issue with pricing from the sales rep is that it is usually dealer net, distributor net, or DN pricing. This means that the luminaire price the sales rep gives to the designer is the price that the electrical distributor will pay the manufacturer. It does not include the electrical distributor’s markup for overhead and profit, nor does it include possible markups by the electrical contractor and/or the general contractor. It is up to the lighting designer to estimate the total markup(s) as well as taxes, shipping and such, and add that amount to the projected lighting fixture budget, but designers have no direct knowledge of what markup these firms will add, nor do we have any control over their markups. The result is that I wind up footnoting my budget with notes like markup percentages are estimated, pricing is based on cost estimates provided by sales representative, and pricing is based on projects of similar size and scope.

Finally, as I explained here, the fixtures that I specify may not be purchased for the project. Once substitutions enter the picture another layer of mystery is added. Yes, it’s complicated. Here’s a flow chart that tries to explain the flow of information (denoted by question marks) and money (denoted by dollar signs) of design and sales relationships. See chapter 9 for a full explanation.

Yesterday my students at Pratt presented custom built lighting fixtures inspired buy the work of a fashion designer. Here are some of them.

Notifications