The current global cyber-attack, combined with last year’s “denial of service attack has me thinking about the lighting industry and IoT.

It was ironic that last year’s attack happened just days before the IES annual conference, at which IoT lighting was touted as the next big thing that everyone had to adopt or be left behind. You may recall that one aspect of that attack was that hackers recruited IoT devices like thermostats and smoke detectors. Many designers may think, “Well, sure, homeowners don’t have good security, but that wouldn’t happen to one of my corporate clients.” The current attack shows the flaw in that thinking. New tools have allowed hackers access to supposedly secure networks, and not all networks that should be secure (such as Britain’s NHS) actually are.

The question, then, is, “Why should my lighting system use IoT?” I’ve asked several friends in lighting design firms large and small and the answers I’ve received are revealing. Almost no one has a client who is asking for this. (I’ve had exactly one client who wanted the lighting system connected to the corporate LAN.) Do they want lighting systems connected to their BMS? If the client is knowledgeable and the building is large, yes, although today’s lighting systems have so many programming options we don’t need the BMS to control the lighting system. Do they want lighting systems to use Wi-Fi so that users can adjust the lights from phones and pads? Not very often. “Why would I want to give that many people authorization to change the lighting?” is the question asked, and rightly so. Do they want light fixtures with IP addresses and built-in Wi-Fi, Li-Fi, daylight sensors, occupancy sensors, temperature sensors, humidity sensors, and software that tracks shoppers or monitors space usage? “How much will that cost?” is the usual first question, followed by a strong “No.”

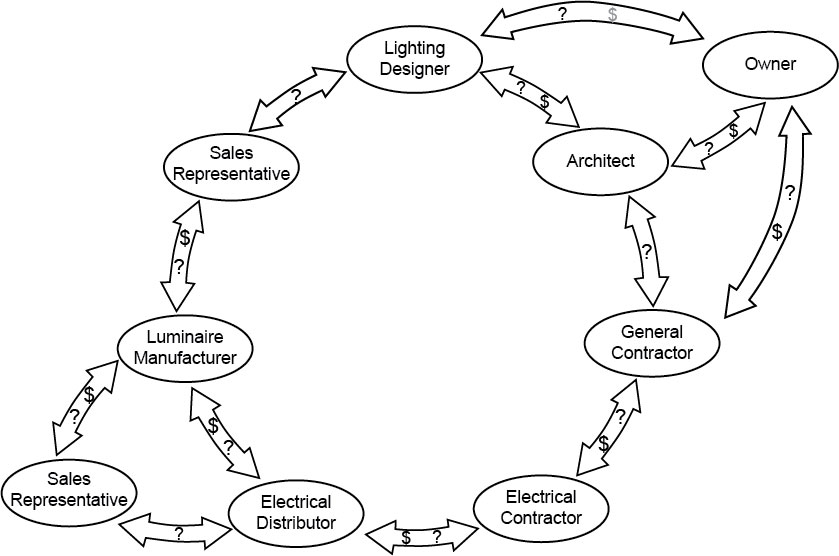

If we designers don’t see an artistic or operational advantage to these systems, and if our clients don’t see an advantage and aren’t asking for these systems, why all the noise about them? The answer, of course, isn’t better lighting design or increased energy efficiency, it’s money. Companies like Cisco see expanded profits from embedding Cisco sensors in every light fixture in a building, connecting all of those fixtures to Cisco POE switches and perhaps controlling the fixtures and sensors with Cisco software. Fixture manufacturers, always looking for a way to differentiate their products, jump on board. Marketing departments create hype, magazines and web sites need material, and voila! the next “must have” lighting system feature.

Who’s providing network security? The corporate IT department, I guess. Are the lighting systems vulnerable to hacking? The current and recent attacks tell us the answer is, “Yes.” Are manufacturers of IoT devices investing in security? Not really. They see it as the responsibility of someone upstream. Would anyone want a lighting system that is vulnerable to being turned off in an emergency, or reprogrammed by someone just to see if they can do it? No.

Some of the lighting systems I am designing are quite complex involving hundreds of fixtures with hundreds of addresses, multiple control protocols, and multiple points of control including touchscreens and Wi-Fi devices. One thing no one has to worry about, though, is high-jacking or corruption of the system. Each system stands alone. Software updates, if they are ever needed, are downloaded and installed via a USB key. Anyone wanting access to the system has to be within Wi-Fi range and has to hack the network. What would they get? Access to a single lighting system. There’s almost no reward and therefore there’s almost no incentive. Call me a Luddite if you like, but for now I’m going to stick to designing secure, flexible systems that provide my clients with only the features that they want at a price they are willing to pay. I’m sure that the pressure to “innovate” will eventually lead me to using these IoT systems. But for security’s sake I’m going to resist for as long as I can.