Here are my comments from last night’s “Celebrating Pratt Authors” event.

Let me say a few words about my book and than I’ll move on. One of the things that drive me to write “Designing With Light” is missing content in other lighting design books. I come from the theatre-both my undergraduate and graduate degrees are in design for the stage, and I worked in the theatre for over a decade before transitioning to architectural lighting. The other two common paths to becoming a lighting designer are from work as an architect or as an electrical engineer. Until now, as far as I can tell, lighting design books have been written by people with those two backgrounds. They do a fine job of discussing how to light architecture and how to calculate illuminance, but none of them actually address the issue of design. None of them discuss how to think about light as a design element in a space, or how to use light to create the desired atmosphere, environment, or ambiance. That’s the void I wanted to fill.

Some of you may know that the United Nations has designated 2015 as the International Year of Light. I want to build on this by saying a few words about the importance of light and lighting design. There’s an old saying, “out of sight, out of mind” but with lighting design the truth is actually closer to “within sight, out of mind.” Too often people ignore or are unaware of the potential that lighting design offers because as long as they can see they’re satisfied. Many people only notice light when it’s beautiful, as with a sunset, or when it’s an impairment, as when there’s not enough light to do what they want to do. Yet, while only a small percentage of people are aware of the lighting in their surroundings, 100% of people are affected by that lighting.

Sight is, without a doubt, our most important sense. Research shows that about 80% of our sensory input, learning, and activities are related to vision.

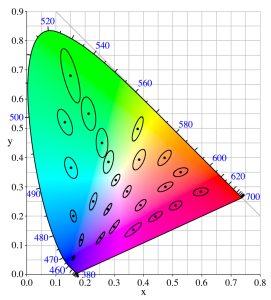

Our visual interaction with the world, and has two components. The first is target or object identification. “I see and apple,” is an example of object identification. However, our minds are much more sophisticated than that. We don’t stop at object identification. We’re not really aware of it, but we automatically go on to evaluate our visual target and its relationship to the surrounding visual field, to our previous experience, and to our expectations. This second component of vision is perception-the identification, organization and interpretation of sensory input. Perception is directly affected by the way light reveals the world to us. Can we see the texture of a material or not? Is the color as expected or is it distorted? Can we see the three-dimensionality or does the object appear flattened? Are details visible or are they hidden in shadow? Lighting design matters, in part, because it affects our perception.

The lighting requirements for object identification in terms of brightness, color, direction, etc. are minimal. However, the effect light has on our perception is huge. Perception causes us to form opinions about, and have intellectual and emotional reactions to, everything we see.

If I were to say that I want to take you to a romantic French restaurant, every one of you immediately has a mental image of that space. You may have a mental picture of the color palette of the room, or the ceiling height, or the spacing of the tables. That image varies from person to person, but there is a remarkable amount of commonality in our expectations. For example, I’ll bet that in your restaurant there’s a candle on the table, that the lighting is dim, and that the wood is dark and polished.

If we walked into a restaurant that we have been told is romantic and find it illuminated like a classroom, the perceptual dissonance between our expectations and our experience would cause us to immediately reject the notion that we were in a romantic restaurant. We would declare that the lighting design was a failure. We would, perhaps, extend the idea of failure to the interior design and, depending on the strength of our emotional response, maybe even to the food. Lighting matters, and understanding how expectations of the users affect their perception is one aspect of creating a successful lighting design.

This is something that I emphasize to my students all of the time – you must understand the intended look and feel of the space before you can light it. I also emphasize that they must understand the distribution of light in three dimensions, not just in a two-dimensional plan view.

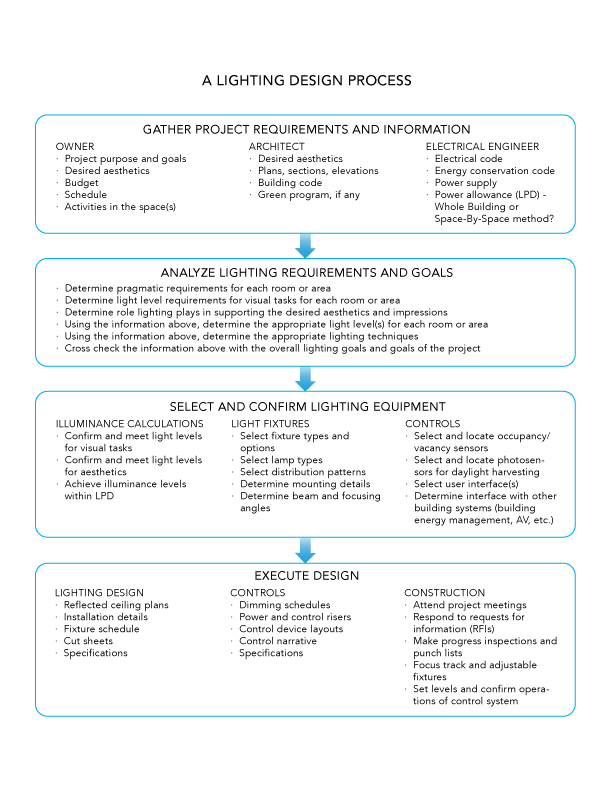

To control the three dimensional distribution of light requires an understanding of the many types of lighting fixtures that are available, and of the light sources that they use. To control those light sources we have to know about dimming and control systems and technology. The body of knowledge required to create a lighting design is very large.

And, it’s getting larger every year. New lighting technologies such as LEDs and OLEDs have some unique properties. To use them well we have to expand our understanding of issues such as color and control technologies. Add to that the fact that energy conservation codes compel us to think much more carefully and creatively about what we do and how we do it because we’re given so little electrical power to realize our design goals.

Add all of this up and we find that lighting design is hard! It requires a solid grounding in light sources, fixtures, controls, and codes. All of that technical expertise has to be combined with a broad understanding of architecture, interior design, lighting techniques, and aesthetics to turn a mental vision or a rendering into a realized design.

I get very excited when I talk about light and lighting, but I’m frustrated, too. Only about 10% of design and construction projects include a lighting designer on their team. For the other 90% of projects, the lighting design is handled by the architect, the interior designer, or the electrical engineer. Yet academia is not providing the lighting education future designers need.

I’ll use Pratt as an example. Not only is lighting design not a required course in the any of the architecture programs, it isn’t even an elective. Students have to go to the Interior Design department if they want a semester of lighting, but that course is going to be eliminated within a few years as the Interior Design department reorganizes. Pratt is just a single example of what I think is an overall disregard or failure to understand the way light affects our experience of the built environment, and the need to teach future designers how to address the entire visual experience. This, of course, takes us right back to “within sight, out of mind.” But, good enough lighting isn’t good enough.

So, in this International Year of Light, I want all of you to think about and talk about the importance of good lighting in your homes, at work, an in the other places you spend your time. If you teach architecture or engineering or interior design, I urge you to give lighting design a place on the curriculum. If you’re a student I want you to demand that lighting design be made a part of your education. The International Year of Light has set the stage, but it’s up to us to act, to raise the importance we place on good lighting.