On November 12 the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) published a position paper on IES TM-30-15. The document is here. It seems to be a willful misunderstanding and misrepresentation of TM-30. Here’s how…

The paper opens with NEMA’s support of an improved color metric but then goes on to say that “NEMA opposes any mandatory reporting or performance requirements for IES-Rf or IES-Rg.” This is a strange opening since neither the IES, in general, or TM-30, in specific, is proposing mandatory requirements. In fact, the IES’s own position paper on this states that “As with any IES Technical Memorandum, TM-30-15 is not a required standard.” So the paper begins with alarm about a non-issue.

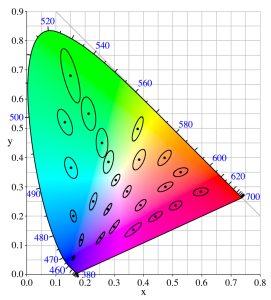

Next, it says that, “Any single-number fidelity measure (such as Ra or the new Rf) that averages the results of many colors in a light source could possibly have a high numerical value and yet perform poorly with some specific colors.” Exactly. That’s the problem with CRI Ra, only a single number is reported. The great advantage of TM-30 is that in addition to the average fidelity value Rf, the calculation tool allows designers to see 1) the fidelity within color groups, called Hue Angle Bins, that encompass the entire color space 2) the direction of hue shift (if any) as displayed in the Color Vector Graphic, and 3) the Rf for each of the 99 Color Evaluation Samples (CES). Far from being a single value, as with Ra, TM-30 provides designers with layers of additional information about the performance of the lamp in question.

In the next paragraph we are told “The IES-Rg metric can have a value greater than 100 and yet saturation might be lower than the reference light source for certain colors.” Right again, but in a misleading way. As with color fidelity, TM-30’s evaluation of color gamut is layered. Rg represents the average shift in saturation of the 99 CES. If a specifier wants deeper information it is available in the calculation tool as 1) a CES chromaticity comparison that plots the CES under both the reference illuminant and the test source so that one can see the shift 2) a graph showing the change of chroma by Hue Angle Bin.

The entire third paragraph complains that if Rf is 100 there can be no increase or decrease in Rg – saturation is held at 100, too. This is like pointing out that the problem with taking a bath is that you get wet and soapy. The interrelation between Rf and Rg is a feature, not a bug. When the fidelity index of a light source matches it’s reference then OF COURSE they will produce the same saturation of colors. If one wants to purposely increase or decrease saturation the only way to do so is to use a light source that is NOT an exact match to the reference source, and hence one that has a lower fidelity value. The relationship between Rf and Rg are shown as a graph in the calculation tool to help designers visualize the values that the tool calculates. That’s a good thing.

Finally, the paper concludes with “It is premature to consider IES TM-30-15 as a mandatory requirement or regulation because the metrics are likely to evolve.” As I said at the beginning, this is a non-issue.

The IES developed and issued TM-30 because CRI does not consistently and accurately represent the color rendering of many light sources, especially narrow band emitters like LEDs. This issue is well known and completely accepted by the industry, including the CIE. (A list of CRI’s shortcomings is included in the latest edition of the IES Lighting Handbook.) The IES position is that TM-30 “has been developed for the benefit of the lighting community to provide: (a) a more accurate assessment of color fidelity; (b) an additional, complementary assessment of the influence of the preferred color appearance of objects (related to color gamut); and (c) more detailed information about the rendition of specific colors.“ and goes on to say that, “the issuance of TM-30-15 will enable the international lighting community to carefully evaluate it, providing a path leading to improved standards and design guidance. Technical analysis and feedback regarding the method described in TM-30 will be critical to continued development and standardization of color quality metrics.” In other words, “We think this is a good tool. We’re publishing it so that other concerned parties can evaluate it. We hope that this will trigger the acceptance of TM-30 or the development of another tool.”

Clearly NEMA as an organization, or members of their Lighting Systems Division, has a problem with the IES issuing TM-30, but the position paper is a red herring. It stirs up alarm over TM-30 becoming a requirement or regulation when the IES has noted that isn’t the purpose of a TM, and attempts to point out shortcomings that actually belong to CRI, not to TM-30. I don’t know about the politics involved here, but I do know that this paper should be read with skepticism.