The Lighting Research Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute recently published a short video in which LRC director Mark S. Rea discusses the costs and benefits of lighting. Here it is.

If you set aside the plugs for the LRC, his statements, and those in his book Value Metrics For Better Lighting, are similar to what I’ve said throughout Designing With Light, which is that it’s the quality of the light and lighting design that are of primary significance while the amount of light that is delivered is secondary. Therefore, the true value of the lighting design is found in the design’s success in meeting the multiple requirements of the owner and the occupants of the space, not in the cost of hardware and installation.

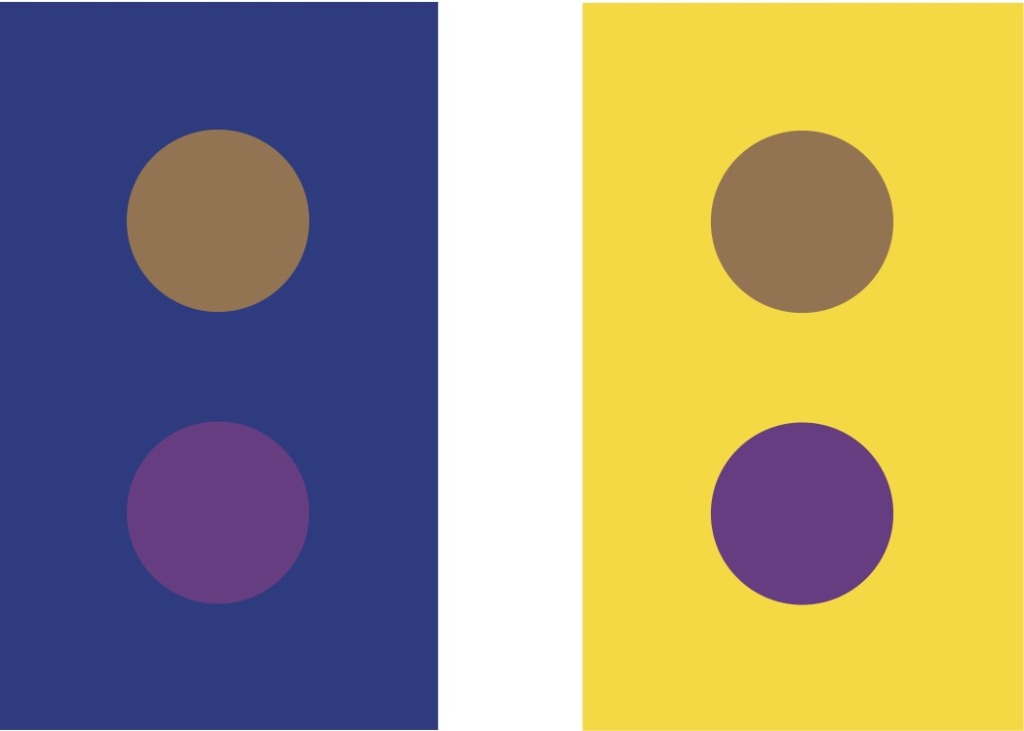

Unfortunately, there are several factors that have created resistance to placing value on thoughtful, appropriately designed lighting. The first is that most people simply do not see light (pun intended). For far too many people, if the light is bright enough for them to see what they’re doing it is acceptable and little or no judgment is made regarding the other factors of lighting design, such as color rendering, providing visual interest, overall effect on occupants, etc. I find that if I show clients or students the difference between light that is adequate for vision and light that creates an appropriate atmosphere or environment they can see it and appreciate the difference. It is also a surprise to them that lighting design can make such a difference in a space.

The second factor is that project budgets are set in dollars with no little or no allowance made for the quality of the design. I have often worked on projects where the project budget and the lighting equipment budget have been set, although design work has barely begun. I understand that a client only has so much money to spend and that has to be respected. However, 1) No bean counter in the world can predict what the design team will develop. Budgets are more appropriately set in coordination with the design team after the design team understands the full extent of the client’s needs and desires. Then, if the projected cost exceeds the client’s budget, informed decisions can be made to pull back on certain aspects of the building’s design or to allocate more money to construct the building the client wants. 2) Spending more money up front on efficient lamps and fixtures, and on controls, can more than pay for itself in savings on energy and maintenance.

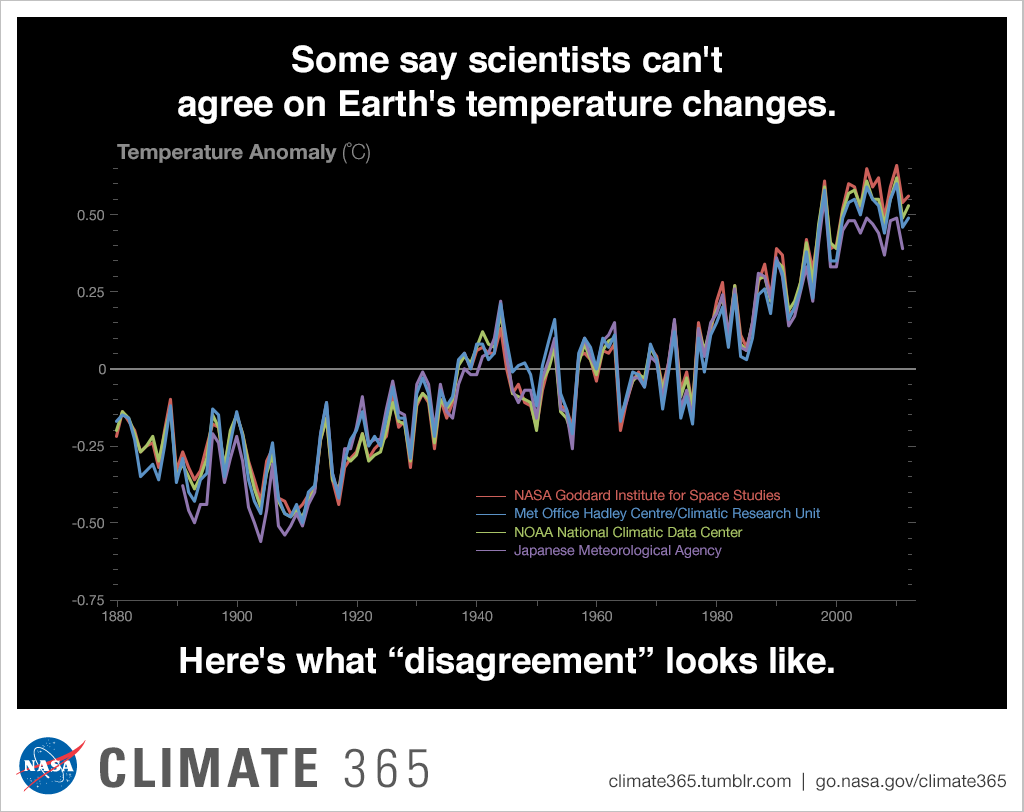

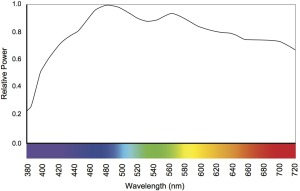

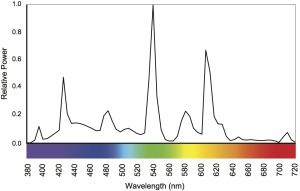

Another factor is that we value what we can measure. Since the early 1900s the lighting design community has invested a great deal in determining how to measure light and on how much light is required for “visual tasks.” Those two aspects became the criteria for evaluating lighting design, and are still presented as primary in many lighting textbooks. In the 1970s John Flynn and others began to study how light can affect the impressions one forms of a space. Later research examined the relationship between a lighting design and those occupying the lighted space including: the affect on worker productivity, absenteeism, and worker retention; student learning outcomes and test scores; retail sales; a light source’s spectrum and clarity of vision; and light’s affect on sleep cycles and other aspects of health. This research has shown over and over again that intelligent, thoughtful, appropriate lighting design can have a significant effect on the occupants and on the owner’s bottom line, whether that bottom line is to make more money, increase student success, or improve health.

Knowledgeable lighting designers can bring so much more to a building than just illumination, yet illumination and lighting design remain synonymous to most of our colleagues and clients. That is part of the reason only about ten percent of construction projects have a lighting designer on the team. Lighting designers and lighting design professional organizations need to do a much better job of educating design team members and our clients about quality lighting design, what it is, and why it matters.