By some estimates less then 10 percent of construction and renovation projects include a professional lighting designer on the design team. Why? Who’s looking after the lighting design? What can the lighting design community do about it?

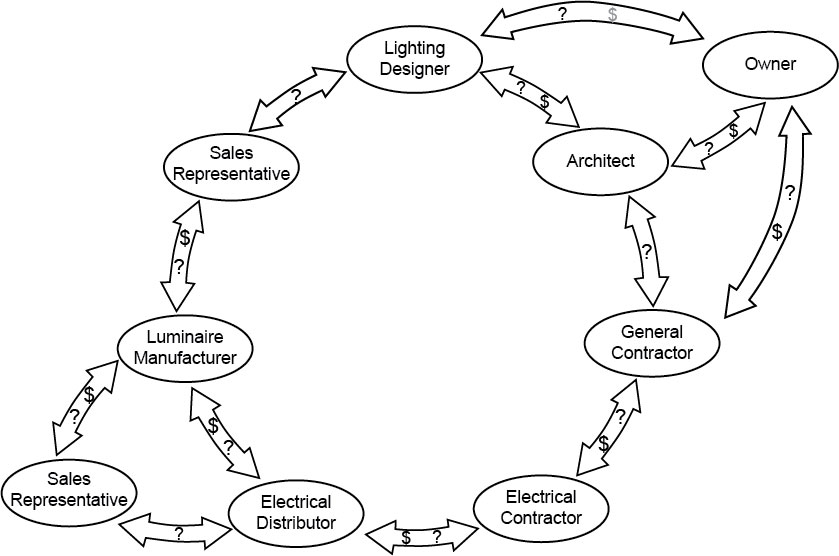

The reasons projects go forward without a lighting designer range from the owner’s lack of understanding of what a lighting designer does to the architect’s desire to keep fees low. These are usually coupled with the belief that other team members can take care of the lighting just as well as well as a lighting designer. The “others” who may provide some or all of the lighting design include the architect, interior designer, electrical engineer, electrical contractor, and lighting salesperson. These other professions can act as lighting designers because the practice of lighting is so young and is unlicensed.

Why should architects and building owners hire a lighting designer? My first answer is, “You’re hiring experts in every other aspect of building design and construction, so why would you NOT hire an expert in lighting, too? Don’t you want the building to look as good as you imagine it will?” My other answers are:

- Research has shown that the benefits of high quality lighting design include increased sales, worker performance, and student test scores.

- Professional lighting designers develop unique designs specifically for each project. They know more about light and lighting, put more time and effort into designing the lighting, and will produce better results than any other team member.

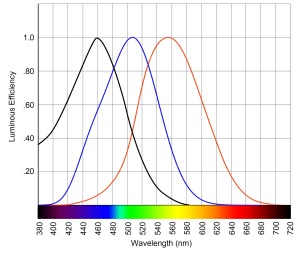

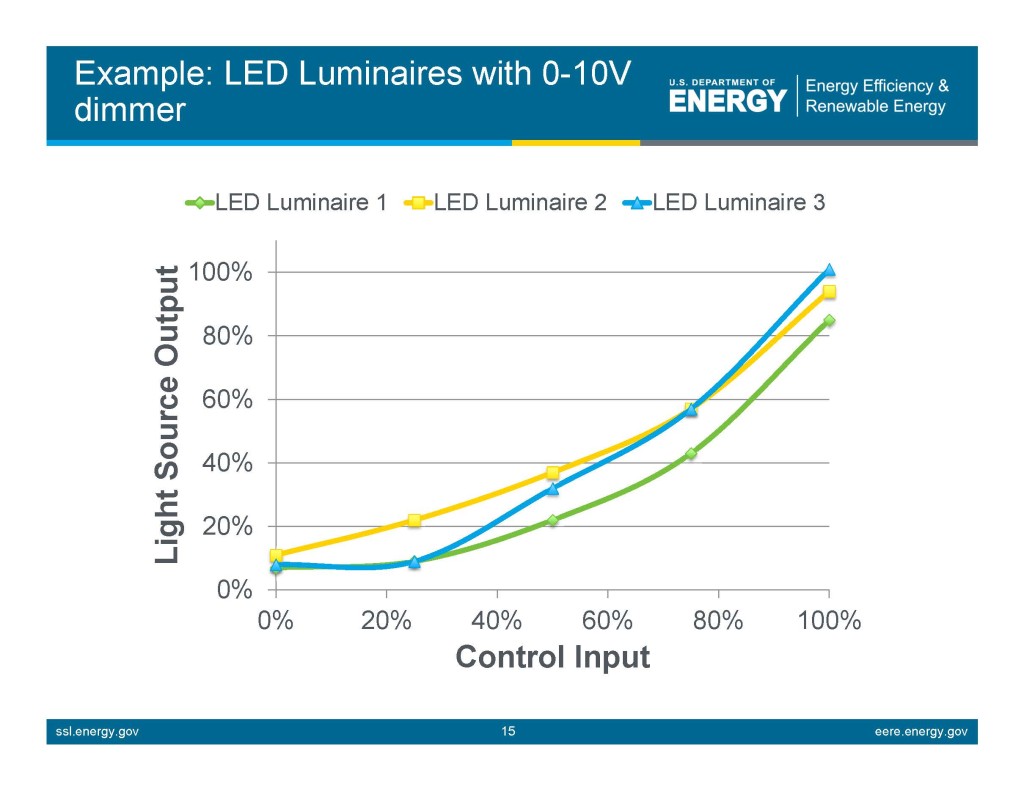

- The lighting industry is moving and changing faster today than at any time since the invention of the light bulb. Lighting designers invest an enormous amount of time and energy keeping up to date on new light sources, energy codes, control systems and the like. No other team member is as well informed about the current state of the field.

What can the lighting industry to do promote the use of lighting designers? It seems to me that our professional organizations, especially the IES and IALD, have to take the lead here because individuals can’t have enough impact. Both organizations do a lot of work within the industry, but I don’t see any outreach to the real decision makers. What could they do? Here are a two thoughts:

- Provide articles to AIA and other professional publications promoting the benefits of working with lighting designers.

- Present seminars and staff booths at conventions of AIA, SCUP, Retail Design Institute and others to promote lighting design.

What do you think? What can we do to promote lighting design?