I recently began a project that includes about 8,000 SF of office space that is completely without windows or skylights. I’ve renovated spaces like this before, and the common complaint from occupants was a disconnect from daylight, weather, and the way they indicate the passage of time. On this project, I determined that the most appropriate solution was to use a light source that rendered colors in a way that is highly preferred to make the spaces more pleasant to occupy and use.

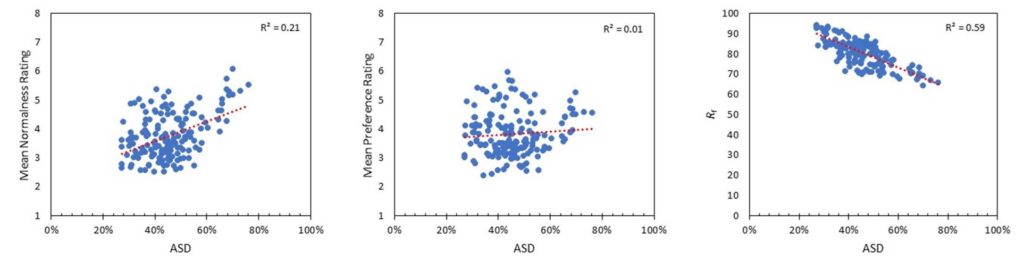

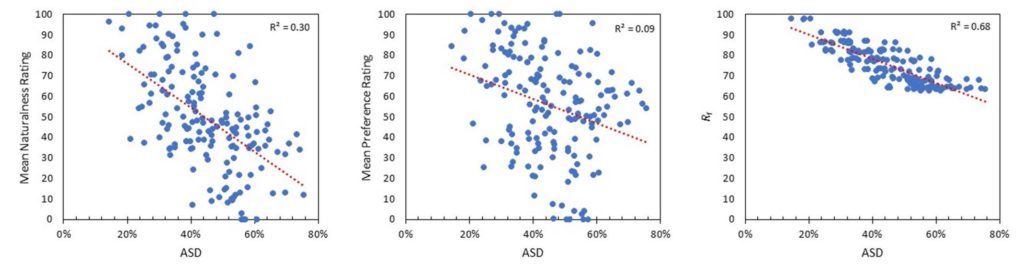

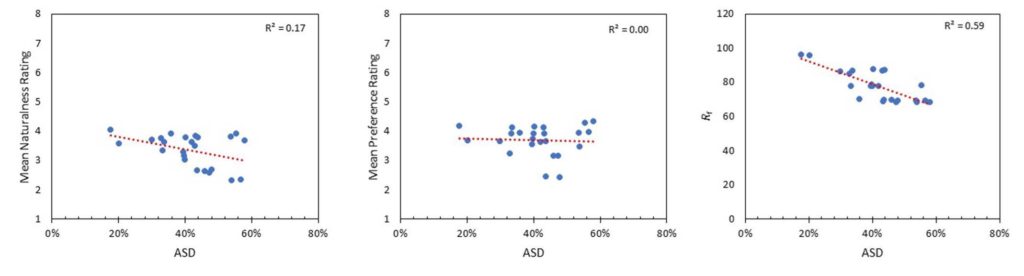

Of course, as a designer who is very knowledgable about color rendering issues and is a TM-30 advocate, I know two things. First, highly preferred is not high fidelity. People prefer a light source that slightly increases the saturation of object colors (especially reds) over a high fidelity source. Second, TM-30’s Annex E provides specifiers with ranges for certain TM-30 measurements that allow us to accurately specify highly preferred light sources.

The task seemed simple enough. Forget about fidelity and find a fixture/LED combination with a spectrum designed for preference, i.e. a light source that meets the TM-30 Annex E specification for a highly preferred (aka P1) light source. After all, we’ve had TM-30 for seven years now, and Annex E for four years. Surely, by now LED manufacturers have introduced products that meet color rendering goals other than fidelity, right? Who wouldn’t see that as a huge marketing opportunity? And surely fixture manufacturers would offer specifiers that LED, again to differentiate their products from the many, many, many similar products from other manufacturers…right?

Alas, the answer is, “No.” One member of the IES Color Committee shared with me a database of over 1,000 LED products, their SPDs, and their various TM-30 measurements, including the Annex E Preference Design Intent. Of those, there are a generous handful of retrofit lamps, most of them by Soraa and Cree, that meet the P1 specification, but only one LED in commercially available linear LED fixtures – Focal Point’s Preferred Light series. That’s it!

Fortunately, this project is for a private firm so I don’t have to worry about developing a three-name or performance spec. Otherwise, I would have to give up on a preferred spectrum and default to high fidelity not because it would be appropriate for the project but simply because there are more options.

I’ve mentioned fidelity and preference. You might be asking if there are other color rendering goals. The answer is, “Yes.” Other color rendering design goals, with brief explanations, include:

Preference. Light distorts object colors with slight increases in saturation, especially reds, in a way that is preferred over the reference light source (that is, preferred over high fidelity). This might be the goal in an expensive restaurant where you want to emphasize the beautiful colors of the food, people, and interior design.

Vividness. Light renders object colors as more or less vivid, or saturated, than the reference light source. Vividness is different from Preference in the degree of distorted saturation and the design intent – making colors pop, not making colors more attractive. This might be the goal in the Skittles store in Times Square where you want the colors to leap out at people.

Naturalness. Light renders object colors as expected, which, surprisingly, is usually not the same as fidelity. This might be the color rendering goal in a grocery store where you want the food to look ripe and appetizing.

Discrimination. Light renders object colors so they can be appropriately sorted. This might be the goal in a facility where even slight color variations must be detected.

Specifiers are captives of manufacturers. We can have design goals oriented toward the needs of the users and the success of the project, but manufacturers only want to sell us fidelity, the same way they’ve been selling us fidelity since CRI was introduced in 1965. For 50 years we only had a hammer (CRI) so all problems were nails (fidelity). TM-30 changed that and it’s time for manufacturers to catch up.